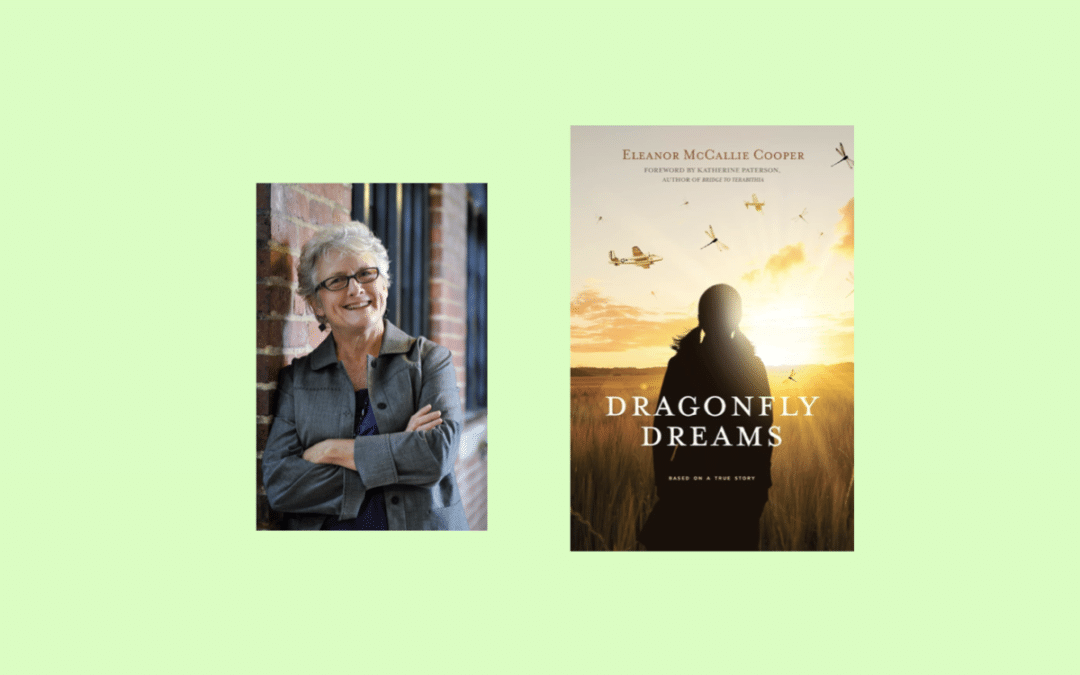

Eleanor McCallie Cooper is drawn by her deep Southern roots to write stories that have been hidden or forgotten. She chronicles families on the edge of traumatic historical events portending personal and social turmoil, and previously co-authored Grace: An American Woman’s Forty Years in China, 1934-74 with William Liu. Eleanor earned a doctorate in education from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga with a focus on community learning and leadership. Her work as a community coach focuses on civic engagement and community-wide visioning. Eleanor lived in Japan for two years and has traveled in Korea, China, India, and many European countries. She lived in New York and San Francisco before returning to her hometown of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

“If a dragonfly lands on you, it means change is coming.

You better watch your dreams, Nini.”

Living in China when the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, Nini and her family don’t realize that their world is about to collapse. Nini and her best friend Chiyoko are on their way home from school when they are stopped by Japanese soldiers and forced to step aside for a car with a mysterious passenger. Uncertain of what is happening, they create a secret hiding place to leave messages for each other.

Nini’s family is soon forced into hiding to protect her American mother from being arrested and sent to an internment camp. When the family situation becomes desperate amid circumstances of hunger, disease, and quarantine, Nini is the only one who can make the dangerous journey across the war-torn city to save her family and find her best friend.

Not since Empire of the Sun has a book captured the drama of Westerners trapped in China during World War II.

1. Your book Dragonfly Dreams is set in China in WWII. Why is it relevant now?

COOPER: Because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The most similar experience to war is a global pandemic. Think about the experience from the view of a child—isolation, staying at home with your parents for an indefinite time, can’t see your school friends, curtailed holidays, quarantine, fear of the unknown, and uncertainty about the future. Pandemics are a mass trauma endured world-wide. When COVID first hit, I knew it was time for Dragonfly Dreams. I hope it will be one of the books that will help young readers relate to their own trauma.

2. Why did you choose to write for young readers?

COOPER: Writing for young readers allowed me to simplify complex historical issues into a universal human story within one family. My protagonist is ten years old at the beginning of the book and thirteen by the end, so I aimed the story for that age group. Holocaust stories set in Europe during WWII are popular with this age group, and this story takes them half way around the world to a place where Americans and Europeans are being sent to internment camps. It will allow a classroom of multi-cultural studies to talk about issues of prejudice and hate from a different perspective. Plus, China is important to this generation. People need to know more, and this story is set when China and the US were allies and needed each other.

3. What inspired you to write this book?

COOPER: It is based on a true story in my family. My father’s cousin Grace married a man from China in the 1930s and was living in China when the Japanese took over in 1941. Foreigners, like Grace, were forced to register, wear arm bands, and then were rounded up and sent to internment camps. She didn’t go to the camps because her family kept her hidden. She continued to live in China after Mao took over and communication stopped. I learned about this story years later, after Nixon opened the doors with China and Grace returned to the US with her son. I lived with her the last year of her life, and her son, William Liu, and I wrote her life story after she died, called Grace in China: An American Woman Beyond the Great Wall, 1934-74.

4. You have written her story as non-fiction and now as fiction in Dragonfly Dreams. Talk about the writing process. How was your experience of writing different as non-fiction and then as fiction?

COOPER: In writing non-fiction, I had excellent primary materials to work with—letters, memoir writing, articles written at the time, and photos. I interviewed people who were alive then. I could weave those rich, personal details with historical facts to create a chronological narrative. When writing fiction, I narrowed the time frame and focused just on WWII. I didn’t have much primary material to work with, but I knew some facts and events that helped shape the story. But to tell the story, I created a character, based on Grace’s daughter who was ten, to be my narrator. I put the story in her voice. Creating a younger narrator helped me break from my own point-of-view. I needed a storyline with emotion and conflict, so I created a best friend. The tension in the story becomes the two best friends wanting to stay connected as the war pulls them apart. The story kept growing and took me places I didn’t expect. I was surprised how much I enjoyed writing once I let go of “telling” the story.

5. What do you consider to be one of the most important messages in Dragonfly Dreams?

COOPER: At the beginning of the book, a dragonfly lands on Nini’s arm and her best friend Chiyoko tells her, “If a dragonfly lands on you, it means change is coming. You better watch your dreams, Nini.” How do we deal with change? We hear expressions today like “the world is coming apart” or “the end of the world as we know it,” but Nini’s world literally collapsed around her. That may be how young people feel today. They want to know if they will make it through the pandemic, the climate crisis, the digital revolution . . . will they remember their passcode? Well, maybe not that one, but I have had trouble lately remembering passwords and it seemed like the end of the world to me at the time.

There are so many changes we can’t control—what will happen to us, to our children? What this story shows us is that children are not encumbered the same way adults are. They will break through and lead us the way Nini knew how to cross the war-torn city and find the help the family needed. She kept her focus on what seemed unattainable. And when it came—when she saw the airplanes flying overhead—she knew in an instant that the war was over. Can we keep our focus? Will we know that change has come when we see it?

6. You started writing after age fifty. What advice would you give?

COOPER: Start earlier! Actually, there are many advantages to writing in your later years. You have fewer distractions from all those big life decisions you had to make in your younger years. You have a lifetime of experiences to draw from, and you may be more reflective, more willing to question things. If you decide to write in these older years, it requires discipline. You have to set a time and place to do it and you have to do it regularly so you don’t forget what you just did. I leave a passage unfinished so the next day I can jump right in rather than start something new. And I leave myself notes—where I am and what I was thinking yesterday. I’m in a writers’ group, so writing is part of my social life. I take classes so I’m always learning new stuff, and I force myself to be on social media, kicking and screaming all the way.